8 October 2019

Finding the Domain Controllers

A significant part of an internal penetration test is mapping the network, and one integral part of this endeavor is locating where the domain controllers are. Locating the DCs is useful for attacking AD, but locating them also tends to shine light on where the critical server subnets of the organization are generally. The tips outlined below are not anything new, but hopefully you find useful during your assessments.

DHCP provided searchdomain

If you’re using DHCP, then you may have been provided a list of DNS servers and a search domain. You can usually find this in Linux by reading /etc/resolv.conf which is populated by DHCP.

A search domain provides your machine with a domain name to append at the end of DNS requests. For instance, if DHCP provided you with the search domain of quickbreach.local and you ran nslookup WORKSTATION7 then your machine will actually attempt to resolve WORKSTATION7, and then subsequently, WORKSTATION7.quickbreach.com. It is for this reason that the search domain is usually that of the FQDN of the domain; Which allows for the DNS resolution of domain connected PCs.

Fortunately Active Directory requires a good number of DNS entries to exist for it to remain functional, and a good way of locating the DCs is to perform DNS lookups on the below entries (Full list and explanation here):

_kerberos._tcp.dc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

_ldap._tcp.dc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

gc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

_ldap._tcp.pdc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

_ldap._tcp.gc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

_kerberos._tcp.dc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

_ldap._tcp.dc._msdcs.<searchdomain>

<searchdomain>

DHCP provided DNS servers

If you’re using DHCP and it did not provide you with a search domain, then hopefully it did provide you with the IP addresses of the DNS servers. These are still useful because often times the DNS server is also a domain controller. You can check this by doing TCP port scans for 88, and if it’s open, that’s probably a domain controller.

If it turns out that the DNS server is not a DC, then hope is not lost. DNS servers usually permit reverse resolution, of which you could do an nslookup of the IP address of the DNS server itself to then be provided back it’s hostname as well as the FQDN. Then you can see the previous technique for finding the DC with the FQDN as the search domain

Additionally, critical servers are usually grouped together on the same subnet, so don’t be afraid to scan for TCP/88 on the same subnet of the DNS servers.

FQDN in RDP Certificates

Alright, so lets say we weren’t provided a search domain and reverse DNS resolutions are not doing anything for you. Another way to find the FQDN to then resolve to find the DCs is to inspect the SSL/TLS certificates protecting remote desktop services on the systems that you can see, such as on the DNS server if you were provided one. It’s as simple as doing a quick port scan for TCP/3389 and opening a web browser to https://IP-ADDRESS-HERE:3389 and viewing the certificate when you’re prompted with an untrusted certificate error. You can accomplish the same thing with curl or sslscan in Linux too.

Leveraging Exchange Subnet

Just a brief note: if you’re still struggling to find the DCs and their other servers in general, try looking for an internally hosted Exchange server by querying the DNS server for the MX records and acting on the results by reverse-resolutions or TCP scans for 88.

Other useful Exchange locating DNS queries include (some of this is guesswork)

_tcp._autodiscover.domain.com

autodiscover.domain.com

mail.domain.com

email.domain.com

owa.domain.com

securemail.domain.com

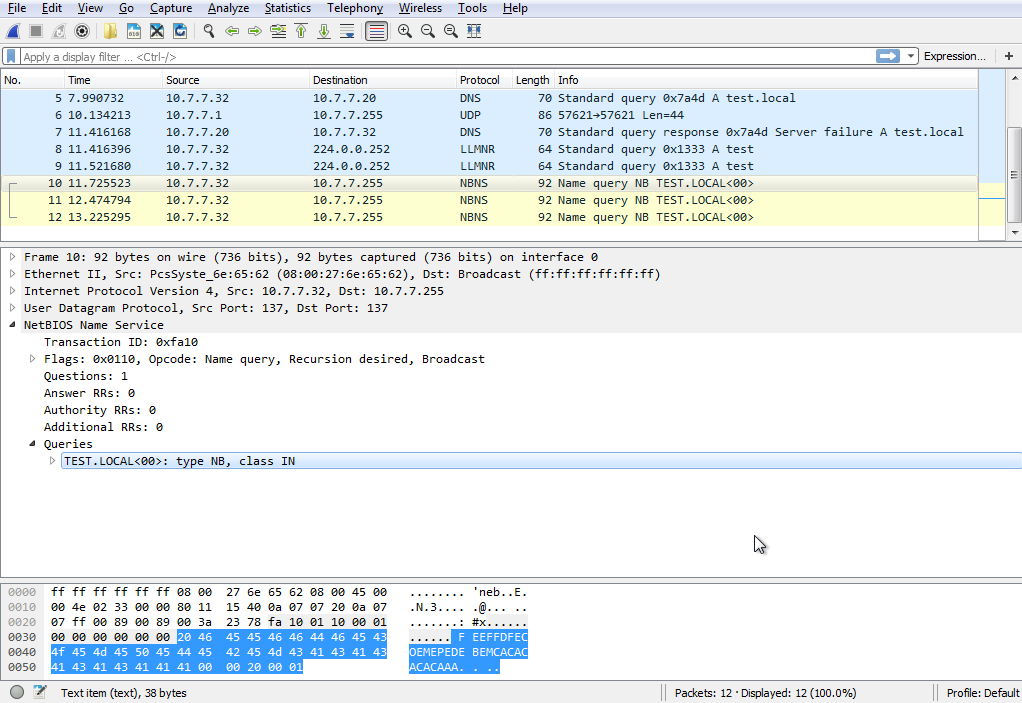

LLMNR/NBT-NS provided FQDN

New scenario: No search domain was provided, no system on the DNS server subnet is a DC, DNS reverse resolutions are disabled, and RDP is blocked on all PCs so you can’t get the FQDN from the certificate.

One more last-ditch effort is to open up Wireshark and look for LLMNR/NBT-NS requests and responses. While we normally love to poison these requests with Responder, for now we just want to observe them to learn about the network.

Above image borrowed from https://pentest.blog/what-is-llmnr-wpad-and-how-to-abuse-them-during-pentest/

From a Domain Connected PC

All of the previous methods were as if you were on the network from a rogue device, such as plugging in a testing laptop during an internal test or through gaining VPN access. It is worth mentioning that if you do happen to have access to a domain joined machine, it is much easier to find the domain controllers. Simply open up the command prompt and run net group "domain controllers" /domain and perform nslookups of the results (remove the dollar sign before performing the nslookup).

There are many other ways to find the DCs from a domain connected PC, but this blog aims to focus on finding them from a more restricted position.

Prime Subnet Signs

If none of the above helped you pinpoint the location of a DC, then you’re pretty much left with manual hunting unless you can compromise a system connected to the domain. TCP/88 is a tell-tale sign that you’re probably talking to a DC, but rather than scan an entire 10.0.0.0/8 for port 88, try DNS zone transfers or reverse resolutions using things like Fierce.

Servers are usually clustered together, so looking for any subnets containing systems with DNS names that include “SQL”, “EXCH”, “MX”, and “DC” are prime suspects.

<-- Back to All Posts

tags: